Repressive Laws Silencing Dissidents, Deviants and Destabilisers in Uganda

Posted: 5 July, 2024 | Author: AfricLaw | Filed under: Contributors, Stella Nyanzi | Tags: Access to Information, Anti-Homosexuality Act (2023), Anti-Pornography Act, Computer Misuse (Amendment) Act, detained without trial, digital rights, Excise Duty (Amendment) Act, free expression, freedom of expression, General Comment 34, human rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), internet democracy without disruptions, Model Law on Access to Information, Musiri David, President Yoweri Museveni, public information, public media, restrictive laws, social media, Social Media Tax Law, state repression, Uganda, Uganda Human Rights Commission, Universal Declaration of Human Rights |1 Comment Author: Stella Nyanzi

Author: Stella Nyanzi

Writers-in-Exile program, PEN Zentrum Deutschland

Fellow, Center for Ethical Writing, Bard College/ PEN America.

Summary

In Uganda, there is an incongruence between the legal regime governing access to information and freedom of expression on one hand, and a barrage of restrictive laws on the other. Although a decade has passed since the African Commission on Human and People’s Rights adopted the Model Law on Access to Information for Africa, growing state repression in Uganda generated laws aimed at silencing, denying access to information, criminalising and penalising government dissidents, deviants or minorities whose behaviours departed from societal norms, and destabilisers suspected of subverting the entrenchment of President Yoweri Museveni’s 37-year-old regime. I triangulate autoethnography with public media content analysis and law review to explore this incongruence within the right of access to information and free expression in Uganda.

Introduction: Arrested for demanding for President Museveni’s academic papers

On 15 December 2020, in the midst of national election campaigns for the presidency, legislators and local council administrators, Musiri David was arrested by uniformed police officers at the Electoral Commission of Uganda (EC) offices where he was waiting for overdue information while lying down in protest on a dirty worn-out mattress. He had returned to the EC after a month of waiting in vain for a response to his request for access to public information necessary for him to assess the fairness of the ongoing presidential elections. Together with three other peaceful protesters, Musiri David, a university student organiser and human rights activist allied to National Unity Platform (NUP), threatened to camp and sleep there until the EC officials gave him access to the file containing copies of the national identity card and academic documents of Yoweri Museveni, the incumbent president who was also the presidential flagbearer of the ruling National Resistance Movement (NRM). Musiri was detained without trial for seven days while undergoing hard labour at Jinja Road Police Station. He was eventually charged with trespass on the property of the EC and being a public nuisance. He was later released on police bond with requirements to routinely report to the police station.

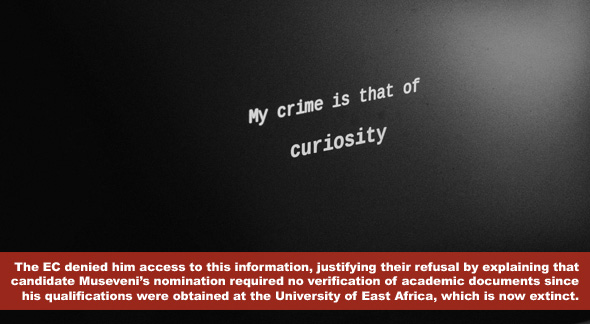

Although Musiri’s peaceful protest actions were criminalised, his demand for access to public information from EC, the public institution mandated with managing the national elections in Uganda, echoed earlier petitions by two lawyers. Firstly, in September 2020, Muwada Nkunyingi (from NUP party) had similarly asked in vain for access to Museveni’s academic documents certifying he met the criteria to run for the presidency as stipulated in the Presidential Act, 2005. The EC denied him access to this information, justifying their refusal by explaining that candidate Museveni’s nomination required no verification of academic documents since his qualifications were obtained at the University of East Africa, which is now extinct. The lawyer responded:

“I could have got that explanation from any lawyer that I trust. What EC should do, is to avail me with papers… The Access to Information Act doesn’t mention that we can’t access documents of the incumbent. We should all be treated fairly.”

Secondly, a month earlier in August 2020, Hassan Male Mabirizi requested the EC for academic documents presented in the 2017 Kyaddondo East byelection by Robert Kyagulanyi who was a parliamentary candidate then and subsequently a presidential flagbearer of NUP in 2021. While Museveni’s presidential nomination documents were withheld from the protester and the petitioner, Kyagulanyi’s documents were instantaneously provided within only four days from the request.

The above contradictory and divergent responses of two public institutions (the Uganda Police Force and Electoral Commission) to varied requests for access to information about public figures highlight the ambivalence, inconsistencies, double standards, and politicisation of the right to access information in Uganda. Furthermore, the arrest and charging of a peaceful protester demanding access to public information held by a state institution illustrate the criminalisation and subsequent repression of free expression by dissident factions of Ugandan society. In this article, I explore and interrogate how the law is used to either restrict or facilitate the right to access information. I start with a synopsis of the legal regime providing for access to information and free expression in Uganda. Thereafter I analyse legislative barriers to the free production, storage and archival, access, and distribution of information within four select laws. Lastly, I examine autoethnographic data about my experience of obstructed access to information held by government institutions in Uganda.

A synopsis of the legal regime governing freedom of expression and access to information

There are several legal instruments for access to information and freedom of expression in Uganda. Below I briefly present available instruments at the international, regional, and domestic levels.

Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights provides for the right to freedom of expression including the right to seek, receive and impart information and ideas through any media and without interference. Article 19(1) and (2) of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) respectively provide for the right to hold opinions and free expression. Article 19(3) establishes a tripartite test for acceptable limitations to free expression, comprising provision within the law, having a legitimate aim; namely respect for rights and reputation, protection of national security, public order, public health or public morals, and absolute necessity. General Comment 34 of the United Nations Human Rights Committee explains the application of these limitations to free expression, as well as expounds on the right of access to information. Several United Nations resolutions were passed to protect freedom of expression on the internet, digital rights, and internet democracy without disruptions to accessing the internet.

At the regional level, article 9 of the African Charter on Human and People’s Rights provides for the right to receive information and to express and disseminate opinions within the law – as a cornerstone for democracy and respect for human rights. The African Commission has elaborated on this right through, among others, the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression in Africa, which was adopted in October 2002 and subsequently replaced by the Declaration of Principles on Freedom of Expression and Access to Information in Africa in November 2019. Additionally, in April 2013, the African Commission of Human and People’s Rights adopted the Model Law on Access to Information for Africa, which stipulates legislative obligations of member states and specifies mechanisms for effecting the right to access accurate information swiftly, cheaply, and effortlessly. Article 25(3) of the African Union Convention on Cyber Security and Personal Data Protection also highlights the centrality of free expression to cyber security laws. In 2016, Resolution 362 on the Right to Freedom of Information and Expression on the Internet in Africa was passed to advance digital human rights. Furthermore, in 2017, the African Commission adopted Guidelines on Access to Information and Elections in Africa. This compendium of instruments forms Africa’s soft-law corpus of Article 9 norms.

Article 41(1) of the Constitution of the Republic of Uganda provides for the right of access to information. It states thus:

“Every citizen has a right of access to information in the possession of the State or any other organ or agency of the State except where the release of the information is likely to prejudice the security or sovereignty of the State or interfere with the right to the privacy of any other person.”

The Access to Information Act (2015) delineates the procedure for obtaining access, and prescribes relevant classes of information that are accessible, thereby exempting records of court proceedings before the conclusion of a case, and records of cabinet and its committees. Additionally, Article 9 of Uganda’s Constitution jointly provides for the protection of freedom of conscience, expression, movement, religion, assembly, and association. A key judicial decision of the Uganda Supreme Court in Obbo & Mwenda v. AG defined freedom of expression as “freedom to hold opinions and to receive and impart ideas and information without interference.”

Against this background of a progressive legal regime providing for access to information and freedom of expression, there also exist diverse restrictive laws – many of which were enacted within the decade since the African Commission adopted the Model Law on Access to Information for Africa. In the following section, I outline a select sample of four restrictive laws.

Laws restricting access to information and free expression in Uganda

The Anti-Homosexuality Act (2023) created the crime of “promotion of homosexuality” which criminalised the production and distribution of information that normalises homosexuality, among other definitions. Upon conviction for promotion of homosexuality, one is liable to imprisonment for up to 20 years, a monetary fine, suspension of a license for ten years, or outright cancellation of a license.

The Computer Misuse (Amendment) Act (2022) enhanced provisions on unauthorised access to information or data, forbade unlawful sharing of information about a child, and penalised the misuse of social media to publish, distribute or share prohibited information. Many government critics were violently arrested, charged, prosecuted, and imprisoned under this law.

The Excise Duty (Amendment) Act (2018) which is popularly called the “Social Media Tax Law” was introduced by President Museveni with the aim of reducing the use of social media platforms for gossip and raising revenue. A tax of Two Hundred Uganda Shillings (UGX 200/=) per day was imposed on using ‘Over the TOP’ (OTT) applications, thereby increasing the costs of internet use and discouraging its appropriation to access information and freedom of expression.

The Anti-Pornography Act (2014) outlawed the production, trafficking, publishing, broadcasting, procurement, import, export, sale or abetting of pornography. Upon conviction, one would be liable to imprisonment for up to ten years and/ or a monetary fine. Furthermore, the court was authorised to suspend internet service providers, publishers, broadcasters, internet-content-developers, dealers in telephone-related-business, etc.

Due to the varying levels of inherent restrictions to the right to access information and freedom of expression, each of the laws above has been contested via court petitions for constitutional consistency, civil protests, or judicial review. For example, on 13 August 2019, a unanimous decision of the Ugandan Constitutional Court ruled that sections 2, 11, 13, and 15 of the Anti-Pornography Act (2014) were null and void for being inconsistent with the Constitution. On 10 January 2023, a unanimous decision of the five judges of the Constitutional Court nullified sections of the Computer Misuse Act (2011) that criminalised offensive communication. In addition, on 3 April 2024, the same court upheld the constitutionality of the Anti-Homosexuality Act (2023), with the exception of sections 3(2)(c), 9, 11(2)(d), and 14 respectively on letting of premises for homosexual uses, failure to report act of homosexuality to the police, and transmission of terminal diseases. Actualisation of the right to access information and freedom of expression will require annulment or amendment of all restrictive laws.

Obstructed access to information held by government: Autoethnography

On 4 January 2019, I suffered a miscarriage during torture when I was a remanded prisoner of conscience in Uganda’s maximum-security prison, on charges of cyber harassment and offensive communication against president Museveni. My personal requests for access to private post-abortion care were denied. On 9 January 2019, while appearing before Lydia Mugambe, a high court judge, I asked for help with the matter. She advised me to avail my antenatal card proving that I was indeed pregnant in prison. She also guided my lawyers to appeal to relevant human rights bodies for intervention. On 10 January 2019, I requested in vain, Gladys Kamasanyu, the magistrate of a lower court to instruct the prison to grant me access to my medical records. However, my requests to the prison’s medical doctor and Officer-in-Charge for my antenatal card and medical reports (comprising medical histories of the repeated HCG pregnancy tests with positive results, receipt of Iron supplements, clinical admission for monitoring because of spotting, scan images and results at the Murchison Bay Hospital and post-abortion pain management administered to me by the director of Uganda Prisons Medical Services) were denied. The spokesperson of Uganda Prisons Services (UPS) issued a press statement assuring the public that I was receiving adequate care from his institution and did not need access to my medical records. This prompted my lawyers to petition the Uganda Human Rights Commission (UHRC) on 16 January 2019 over the violation of my rights to healthcare and information even when I was in prison, leading their investigators to come to the prison to assess my health status. On 17 January 2019, I refused to cooperate with prison staff responsible for transporting me to court, unless I was given my medical records. Separately, the president of Uganda Medical Association (UMA) and the regional coordinator of the International Red Cross (IRC) also visited me in prison and made a case for the prison to give me access to my medical information as a precursor to ensuring that I received appropriate healthcare. Subsequently, a family doctor was allowed to visit me in prison, assess my health status and prescribe requisite medication and diet – all conducted in the presence of prison medical staff. However, my medical records remained withheld from me, even after I sought intervention of the lower and high courts, UHRC and UMA. Similarly, my requests to UHRC for a copy of the report of their finding from the investigations they conducted at Luzira Women Prison remain unanswered to date – four years since my release upon acquittal in February 2020.

The foregoing autoethnographic material from a widely publicised case of intentionally obstructing access to information highlights how different government agencies in Uganda including the prison, lower court and UHRC colluded together to deny me access to information requisite for urgent medical care. This information was not only essential evidence that I was pregnant in prison, but that I also lost the pregnancy during torture by prison wardresses and received healthcare for both antenatal and post-abortion complications from the prison medical services. The withheld information would foment my repeated accusations that the executive in Uganda appropriated prisons services to torture government critics, members of opposition political parties and dissidents such as myself. Moreover, if a person with relative privilege (including access to legal representation, ability to obtain counsel from judicial officers even when I appeared before them as a remanded prisoner, having support of leading medical experts in the UPS and UMA, access to appellant bodies including UHRC and IRC, with sustained interest of local journalists and foreign correspondents, etc) was unable to obtain access to this important information held by government agencies, how much worse is the situation for other Ugandan citizens?

There is an incongruence between the legal regime governing access to information and freedom of expression on one hand, and routine repressive state practice in Uganda. Individuals marked as dissidents, deviants and destabilisers are routinely denied access to information held by government agencies; thereby being silenced and disempowered from acting based on recorded evidence.

About the Author:

Stella Nyanzi is a scholarship-holder of the Writers-in-Exile program of PEN Zentrum Deutschland and a fellow of Centre for Ethical Writing jointly convened by Bard College and PEN America. She obtained her PhD from London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine in 2009, MSc. in Medical Anthropology in 1999 and BA Mass Communication and Literature from Makerere University in 1997. She is also a published dissident poet, avid social media commentator, social justice activist and politician belonging to Uganda’s opposition political party called Forum for Democratic Change. She was the first Ugandan to be convicted to 18 months in maximum-security prison under the Computer Misuse Act. Upon her acquittal after serving 16 months at Luzira Women Prison, she became an ardent advocate for free expression and access to information.

[…] of judicial independence in societies in the process of democratization, the repeal or amendment of oppressive laws, and the establishment of mechanisms for accountability, including independent commissions of […]