Sexual and gender-violence against women in the Sudanese conflict

Posted: 22 April, 2024 Filed under: Joris Joël Fomba Tala | Tags: conflict, gender-based violence, human rights, International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, International Humanitarian Law, rape, Rapid Support Forces, refugee women, reproductive health, Sexual and gender-violence, sexual violence, socio-economic development, Sudan, Sudanese conflict, torture, United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel and Degrading Treatment or Punishment, women’s rights Leave a comment Author: Joris Joël Fomba Tala

Author: Joris Joël Fomba Tala

Researcher, Centre for International and Community Law

Introduction

The conflict that broke out in Sudan (Republic of Sudan) on 15 April 2023 between two rival military factions has had disastrous consequences for women. Dubbed the “war of the generals”, the conflict pits Sudan’s armed forces against the Rapid Support Forces (RSF). In its 2024 report, UNFPA said it was very concerned about the escalation of cases of gender-based violence in the Sudanese conflict. This particularly alarming against the background of an already dire situation of women’s rights in Sudan before the outbreak of hostilities, as the Special Rapporteur on violence against women reported about Sudan in 2016. Almost a year after, the fighting continues in the main cities of Sudan, but the fact remains that Sudan still has no functioning government. UN Women says it is “shocked and condemns reports of increasing gender-based violence in Sudan, including conflict-related sexual violence against women and displaced and refugee women”. In the same vein, UN Women Africa expressed its deep concern about the serious consequences of the Sudanese conflict on women and girls and called for immediate action against the violence they face. However, in a context of armed confrontation, it is undeniable that both parties do not respect international legal standards and commit serious violations against women and girls. This article discusses the application of the relevant legal rules for the protection of women applicable to the Sudanese conflict. The first section will identify these rules. The article will then analyse the various forms of sexual and gender-based violence prevailing against women and finally make proposals for better protection of women in the Sudanese conflict.

Overview of the legal framework for sexual and gender-based violence

In international humanitarian law (IHL), the rules governing the behaviour of parties to a conflict vary according to whether the conflict is international or non-international in nature. Some commentators have plausibly and obviously maintained that the clashes in Sudan amount to a non-international armed conflict (NIAC) by virtue of Article 3 common to the 1949 Geneva Conventions (GC) and Article 1(1) of Additional Protocol II, because the fighting in this case was between government forces and a dissident armed group who is non state actor. In any event, the relevant rules of IHL apply in the context of the Sudanese conflict. IHL provides a general framework for the protection of women in both international and NIAC. It is important to point out that Protocol II of the GC creates obligations for government forces and also applies to dissident armed forces in accordance with article 1 paragraph 1.Consequently, the Republic of Sudan has an obligation to ensure that the rules relating to IHL are respected by the Rapid Support Forces (RSF).

Under customary international law, the international human rights law (IHRL) rules apply at all times (here, paragraph 216 and 217; here, paragraph 24; here, paragraph 106). For the purposes of this study, it is therefore appropriate to analyse the relevant human rights rules that prohibit sexual or gender-based violence and to which the Republic of Sudan is a State Party (here). Thus, the United Nations Convention against Torture and Other Cruel and Degrading Treatment or Punishment and the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights will form the legal basis for the discussion on IHRL in this essay. Rape, which can cause severe pain and suffering, as recognised by the Appeals Chamber of the International Criminal Tribunal for the former Yugoslavia (ICTY), was held to amount to torture in the Kunarac case (Paragraph 150). In addition, sexual and gender-based violence may have consequences for other rights enshrined in the Covenant, in particular the prohibition of slavery (Article 8) and the right to liberty and security (Article 9). Even if these human rights treaties do not contain specific prohibitions on sexual and gender-based violence, the Report of the Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel and degrading treatment suggests that these have acquired the status of jus cogens, from which no derogation is permitted. Every aspect of women’s lives is affected by conflict, which often results in the destruction of the family fabric, socio-economic development and reproductive health of women.

Serious gender-based violence against women in the Sudanese conflict

Acts of rape

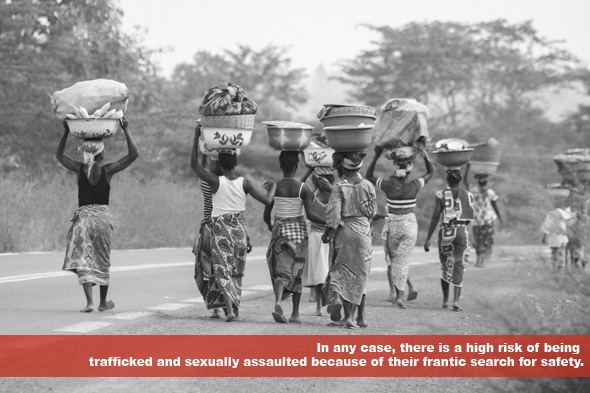

Many women in the Sudanese conflict are victims of rape. It has been reported that women were raped mainly in the cities of Khartoum and Darfur. For example, some NGOs reported recording 124 alleged cases in Khartoum between April and June 2023, while Human Rights Watch reported that it recorded 78 cases of rape in Darfur for the same period. Numerous accounts of rape committed by RSFs were reported. For example, according to the reports, 221 women and girls were raped in the town of Tabit. Faced with this violence, many women fled Sudan for neighbouring Chad. For them, the risk is high throughout the journey and can compound the trauma already experienced in their country of origin. In any case, there is a high risk of being trafficked and sexually assaulted because of their frantic search for safety.

This situation is exacerbated by the fact that hospitals are bombarded by the parties to the conflict, preventing women from receiving care. In fact, at the start of the conflict, the WHO recorded 50 attacks on health facilities. It has to be said that the rapes committed by the RSF sometimes lead to pregnancies, and medical monitoring of the mother and baby is virtually impossible. As a result, there is a risk to the health of the baby, who could be born prematurely or die after delivery.

Ethnic-based sexual violence

Tribal militias allied to the RSF have joined the conflict. Non-Arab women are particularly targeted by the RSF in the Sudanese conflict. For instance, many of women from the Massalit ethnic group have been targeted. It has been reported that attacks have particularly targeted women from the town of El Geneina. According to NGO reports, some of the victims who were interviewed said that the attackers had explicitly mentioned their identity while making threats against non-Arabs. It has been reported that ethnicity plays significant role in gender-based violence on ethnicity committed by RSF in Darfur. According to the UN High Commissioner’s report, this ethnic-based violence leads to other violence, including torture.

Measures taken to put an end to sexual and gender-based crimes

At the time of writing, the Office of the Prosecutor of international criminal court (ICC) is conducting in-depth investigations into crimes falling within its jurisdiction in the Sudanese conflict. It should be noted that in Resolution 1593, the Security Council referred the situation in Darfur to the ICC since 2022. In view of the seriousness of the crimes committed in the conflict in Sudan, the Office of the Prosecutor is committed to prioritising investigations into sexual campaigns of mass rape, while ensuring that the “effects of the law are felt in real time”. With regard to the nature of the crime and the victim, the Office of the Prosecutor could take into account the specific nature of sexual violence as an aggravating circumstance at the time as acknowledged in the Ongwen case (paragraph 8). In addition, discrimination against women because of their ethnicity could also be considered as an aggravating circumstance. Finally, in the case of rape convictions, the long-term consequences on the mental, physical health and the families of female victims particularly as regards the children born of these rapes should be considered as aggravating circumstances. It is important to note that sexual and gender-based violence have been recognised by the ICC as war crimes and crimes against humanity (Article 7 paragraph (1) (g) of Rome Statute). Consequently, violence against women resulting from the fighting underway in Sudan could constitute war crimes (Article 8 (2) (b) (xxii) and ethnic-based gender-based violence (Article 7 (1) (h).

About the Author:

Joris Joël Fomba Tala holds a PhD in public international law from the University of Douala in Cameroon. As a former fellow at the winter courses of The Hague Academy of International Law, he is interested in issues relating to international humanitarian law, international criminal law, the law of the use of force, international responsibility, human rights and international terrorism. He is also a former postdoctoral fellow at the Max Planck Institute for Comparative and International Law in Heidelberg, Germany. He is currently a researcher at the Centre for International and Community Law at the University of Yaounde 2 in Cameroon.