Enforcement of lockdown regulations and law enforcement brutality in Nigeria and South Africa

Posted: 23 June, 2020 Filed under: Folasade Abiodun, Mary Izobo | Tags: accountability mechanisms, apartheid, coronavirus, COVID-19, enforcement officials, human rights violations, lawlessness, lockdown, lockdown regulations, medical facilities, Nigeria, pandemic, public health, public health interest, right to freedom of assembly, South Africa, use of force 1 Comment Author: Mary Izobo and Folasade Abiodun

Author: Mary Izobo and Folasade Abiodun

(An earlier version of this article was published by Daily Maverick)

Since January 2020, COVID-19 pandemic, has held the world to ransom and has posed a threat to public health. It has put a lot of pressure on available medical facilities with a record of more than 9 million persons infected and more than 470 000 deaths globally with numbers set to increase. In order to stop the spread of the coronavirus, several countries are taking measures such as the closure of airports, seaports and land borders, isolation and quarantining of persons, banning of religious, sporting and social gatherings, closure of schools and universities, restaurants, public spaces and complete or partial ‘lockdown’ of some countries. The lockdown of countries entails complete restriction of movement as the virus is transmitted through direct contact with infected persons or surfaces. Some of these measures as well as their enforcement , have implications on the right to freedom of movement, the right to freedom of association and the right to freedom of assembly.

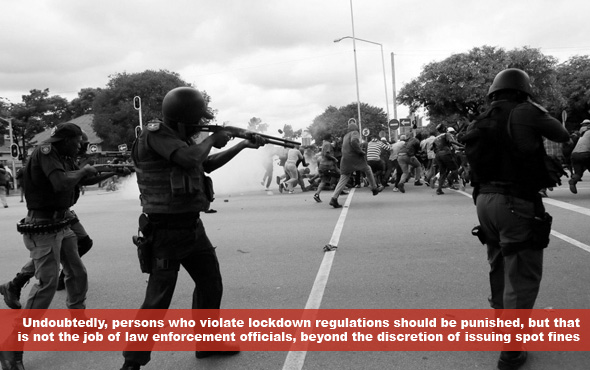

Almost all countries in Africa have been affected by COVID-19. Most of the affected African countries have invoked restrictions highlighted above. The police, and in some cases the army, have been called upon to enforce compliance of the lockdown regulations. However, the enforcement of these regulations by law enforcement officials have generated a lot of controversies and public outcry as there have been severe violations of human rights.

As former colonies with long and difficult histories of war, several countries in Africa have had a history of violation of human rights and brutality by law enforcement officials. Two countries of note are Nigeria and South Africa. The arbitrariness and lawlessness sometimes perpetrated by law enforcement officials in these countries is not new nor peculiar to the present pandemic. This can be traced to the culture of militarism in Nigeria and South Africa as both countries have long histories of military regime and apartheid rule respectively. It is safe to say that law enforcement officials are locked in an aggressive mode whenever they are called upon to enforce and or defend national interests at the detriment of the populace they are supposed to protect. History shows that law enforcement officials in these two countries are used to forceful and violent means of enforcing the law and have adopted a muscular approach to alleged violators of the lockdown regulations.

Nigeria is experiencing its longest uninterrupted period of democratic rule since it gained independence in 1960. From 1966 to 1979 and 1983 to 1999, Nigeria was led by the military junta that used the military as a tool to ensure and mandate cooperation from citizens by the use of force. These periods were marred by gross violation of human rights by the military in Nigeria. In the wake of COVID-19 pandemic, Nigeria took measures to contain the spread of the coronavirus by restricting movement in order to contain the spread of the virus. Movement was restricted in several states, including the Federal Capital Territory, Abuja. The National Human Rights Commission of Nigeria (NHRC) received 105 complaints of human rights violations against law enforcement officials and at least 21 people were reported killed by law enforcement officials between 30 March 2020, the commencement of the lockdown and May 2020. One of such unfortunate incidents, is the gunning down of a man by a law enforcement agent in Delta state, who was going about a legitimate errand of getting drugs for his pregnant wife as permitted by the lockdown regulations.

South Africa on the other hand, experienced a system of apartheid that upheld institutionalized racial segregation and white supremacy from 1948 to 1994. The police and the military were used as tools by the government to forcefully remove black South Africans from areas designated as “white” to the homelands, terrorised and violated the rights of Black South Africans with impunity. The Apartheid period gave the police and military excessive powers and carte blanche to brutalise and torture citizens. Faced with the threat of COVID-19, President Cyril Ramaphosa declared a state of national disaster and a complete lockdown of the country, enforced by the deployment of the police and the military. The lockdown started on 27 March 2020, and by the end of May 2020, at least 230,000 people had been charged for lockdown-related offences. In addition, there have been 39 complaints of murder, rape, corruption, use of firearms under investigation and at least ten people have been reported killed by law enforcement officials. One notable event concerns Sbusiso Amos, who was followed home by law enforcement officials and shot in the veranda of his house for allegedly being found drinking alcohol at a local tavern during the lockdown, injuring children aged 5 and 6 years in the process.

Law enforcement officials in Nigeria and South Africa are reported to have assaulted, tortured, denigrated, unlawfully arrested, seized and looted properties, extorted and carried out corrupt practises in the enforcement of lockdown regulations. Both countries have been listed and slammed by the United Nations for their heavy-handed enforcement of lockdown regulations. Citizens going about their legitimate businesses without flouting the lockdown regulations are not exempted from the ruthlessness of these law enforcement officials. These law enforcement officials have abused power, deployed disproportionate use of force, and have blatantly undermined national and international laws. It is apparent that after years of military rule in Nigeria and Apartheid in South Africa, violence by law enforcement officials remains an ‘acceptable’ way of treating the populace – a sad reality of both countries’ bitter, barbaric, and dark past. The enforcement of the lockdown regulations by law enforcement officials shows that the problem of police brutality is rife and a major weakness in policing in Africa.

Undoubtedly, persons who violate lockdown regulations should be punished, but that is not the job of law enforcement officials, beyond the discretion of issuing spot fines (which themselves may be challenged in court). Law enforcement officials have been deployed to maintain peace and order and arrest persons who engage in prohibited activities. While law enforcement officials are allowed to use force in the performance of their duties, they must comply with the national and international standards of necessity and proportionality in the use of force. Breaching the law does not necessitate arbitrary force in return from law enforcement officials. There is the need to strike a balance between protecting human rights and the public health interest that the restriction regulations seek to protect.

Reasonable and proportionate force may be used in ensuring compliance without having to violate human rights in the process. Additionally, accountability mechanisms should be put in place in the event of an erring state actor who violates human rights. Accountability mechanisms should be unambiguous in the treatment of reports of violence by law enforcement officials. An avenue for reporting abuse is not enough without an assurance that such reports will be transparently and impartially investigated and those found in violation of human rights appropriately punished to serve as a deterrent.

About the Authors

Mary Izobo is a human rights lawyer with experience in the field of human rights, governance, and rule of law for development. She holds a Bachelor of Arts (BA Hons) in French Language from the University of Ibadan, Nigeria; Bachelor of Laws (LLB) from the University of Aberdeen, Scotland, United Kingdom; Barrister at Law (BL) from the Nigerian Law School, Abuja, Nigeria; a Master of Laws (LLM) in Human Rights and Democratisation in Africa from the University of Pretoria, South Africa; and a Master of Laws (LLM) in Rule of Law for Development from Loyola University Chicago, United States of America. She is currently a Doctor of Laws candidate with a focus on governance in Africa at the University of Pretoria, South Africa.

Folasade Abiodun is a lawyer and a researcher within and outside of Nigeria with interest in enhancing ‘development’ through the instrumentality of law. She holds a Master of Laws degree in Rule of law for development. A part of her recommendation in her research work has been adopted to resolving existing challenges.

[…] Supply hyperlink […]