Back to Basics: From the medical model to the social model of disability rights – where are we now?

Posted: 26 August, 2024 | Author: AfricLaw | Filed under: Neville Mupita | Tags: disability rights, environmental barriers, human rights frameworks, legislation, medical condition, medical intervention, medical model, ongoing challenges', persons with disabilities, policies, rehabilitation programs, social model, societal barriers, subversive oppression, unemployment rate, United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities |Leave a comment Author: Neville Mupita

Author: Neville Mupita

Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria

In recent years due to the growing recognition of the need for a paradigm shift, the international community has witnessed major progress in advancing the rights of persons with disabilities. This is a shift from viewing disability as a medical condition or an inherent deficit to a view that understands that disability is a result of environmental and societal barriers. The reimagining of disability was and is a practical necessity as it plays a major role in legislation, policies and everyday interactions.

From the medical model to the social model

Traditionally, people have viewed disability through the medical and deficit-based lens with a focal point on the individual’s impairment as the problem. This approach implies that the intrinsic issue is the person’s impairment, which requires medical intervention to be ‘fixed’, suggesting that something is ‘wrong’ with the person.

Focusing on one’s impairment excludes persons with disabilities from mainstream society. The medical model of disability is evident in schools where children with disabilities are labelled and segregated in what are often termed as special classes or schools instead of altering or adjusting classes and teaching methods to be inclusive. The medical model perpetuates the segregation of persons with disabilities in facilities designed to isolate them; denying them employment opportunities and participation in society, reinforcing the view of disability as abnormal. Such subversive oppression makes persons with disabilities less likely to contest their exclusion from society.

However, as understanding of disability has evolved, so too has the approach to addressing it. The paradigm has since shifted to what is termed the social model of disability which is broadly embraced in the human rights frameworks. This model contends that disability is a result of the interaction between an individual and a society that fails to accommodate their needs. It asserts that physical, systematic, and attitudinal barriers that hinder an individual’s full and effective participation on an equal basis with others in society are what truly disables the person, not the impairments themselves. A core tenet of the social model is listening to the perspectives of persons with disabilities which provides a net of sorts in capturing the complicated disability experiences and their interaction with the environment. The view projects that if the barriers are removed then life choices for persons with disabilities are not restricted, leading to independence and equal inclusion for persons with disabilities in mainstream society.

An example of the social model is evident in the design of public transportation systems. Instead of focusing on the individual’s mobility impairment, the social model advocates for adjustments and alterations to the environment to ensure that trains, buses, and stations are well-equipped with ramps, elevators, and priority seating. This way the physical barriers are removed, and the system becomes accessible and enables independent travelling for persons with disabilities.

Building on the social model, the human rights model of disability further advances this perspective by asserting that persons with disabilities have the same rights as everyone else in society and shall not be discriminated against on the grounds of disability or any other grounds. This model emphasises that persons with disabilities are not to be viewed as ‘objects of charity, medical treatment, and social protection’, but rather as equal members of society entitled to the same rights and opportunities as everyone else.

This paradigm shift is embodied in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), adopted in 2006. Article 1 of the CRPD provides that “[p]ersons with disabilities include those who have long-term physical, mental, intellectual or sensory impairments which in interaction with various barriers may hinder their full and effective participation in society on an equal basis with others”. The definition asserts that challenges faced by persons with disabilities stem from societal barriers and not from the impairment itself. Further, the CRPD provides that states must remove barriers and promote accessibility of opportunities that are inclusive for persons with disabilities allowing them to participate in society and enjoy their fundamental rights on an equal basis with others.

Challenges in implementation and the way forward

Despite the ratification of the CRPD by many states and the incorporation of its provisions and the social and human rights models into their domestic laws, the effective implementation of these laws appears to be lacking or misunderstood. Though states accept the social and human rights model and understand that the problem is the environment, the solutions are still targeted at persons with disabilities.

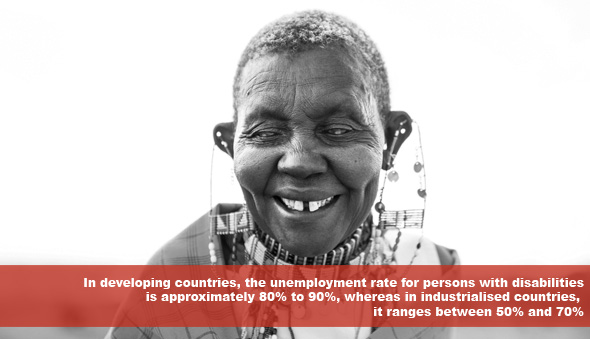

For example, in developing countries, the unemployment rate for persons with disabilities is approximately 80% to 90%, whereas in industrialised countries, it ranges between 50% and 70%. In trying to solve the problem of unemployment for persons with disabilities, more resources are allocated to special training and rehabilitation programs and initiatives aimed at preparing individuals with disabilities for the labour market. Yet lack of accessible workplaces undermines such efforts. Infrastructure that is inaccessible such as offices lacking assistive technology, and building with no ramps or elevators, prevents qualified candidates from securing employment. Though states understand the social and human rights model of disability, state policy implementation overlooks the root cause of the problem, which is the environment that is inaccessible and hinders persons with disabilities from meaningful work.

At the heart of the ongoing challenges to the implementation of disability rights lies this disconnect between understanding the problem and targeting the solution. While the discourse of disability has shifted through the CRPD, the failure to fully embrace and operationalise the social and human rights model in policy implementation means that persons with disabilities continue enduring barriers to equality and inclusion. To create a truly inclusive society, states must take proactive steps and move beyond simply acknowledging the need for accessibility in dismantling persisting challenges faced by persons with disabilities.

In conclusion, while states have acknowledged the paradigm shift from the medical model to the social and human rights model of disability, much work remains to ensure the inclusion and protection of the rights of persons with disabilities. The real change lies in the effective implementation of policies and laws that embody the social and human rights model. Through a comprehensive approach and focusing on changing societal attitudes, altering the environment, and ensuring all sectors of society accommodate the needs of persons with disabilities; we can move closer to a world where disability is not a limitation but part of the rich diversity of humanity.

About the Author:

Neville Mupita is an advocate for social justice and human rights. He is an LLM in Human Rights and Democratisation in Africa candidate at the Centre for Human Rights, University of Pretoria. He holds a Bachelor of Arts in Law (with distinction) as well as an LLB from the University of Pretoria.